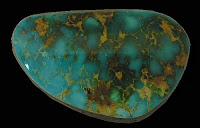

Blue Gem turquoise Cabochons are rare, valuable and historic American treasures. Quality Blue Gem turquoise is gifted with a wide range of color all of which are striking, full of wonder and pleasing to the eye. Because Blue Gem turquoise cabochons are very hard, a high polish is associated with this stone and unlike most turquoise, they don't easily change color. Very little large material ever came out of the Blue Gem mine. The majority found was small 1-mm "bleeder" veins and tiny nuggets which were perfect for Zuni inlay as well as their fine needlepoint and petitpoint jewelry. Blue Gem turquoise was very popular in the late 1930's and 40's and was commonly used in the Fred Harvey "tourist jewelry" that is so collectable today.

The Blue Gem turquoise deposit was first noted by Duke Goff in 1934. It was subsequently leased from the Copper Canyon Mining Co. by the American Gem Co. of San Gabriel, CA., owned by Doc Wilson and his sons, Del and William. The company operated the property until 1941 when the outbreak of the war caused a shortage of experienced miners. Both Del and William Wilson were called into the Army for the duration of the war, thus forcing the mine to close. Subsequently, the lease was allowed to lapse and work was abandoned. In 1950, the mine was leased by Lee Hand and Alvin Layton of Battle Mountain.

Production of turquoise at the Blue Gem lease in the early days of the operation was enormous. Although there is no exact information, it is reported that the output amounted to nearly $1 million in rough turquoise. The mine is still active, although it is currently in the center of a major copper deposit being developed by Duval Corp.

The Blue Gem mine was at one time located deep underground, accessed by tunnels descending as far as 800 feet. This is of interest because the Blue Gem Mine and the Bisbee Mine in Arizona are the only two mines (of which we are aware) that turquoise was found that deep in the earth. The Blue Gem mine was once consisted of extensive underground workings and open stopes. An adit several hundred feet long on the main structure connected to numerous shorter tunnels and several open stopes. Directly above the main adit was a glory hole some 100 feet long.

Blue Gem turquoise occurs in argillized quartz monzonite cut by two limonite-stained sheer zones, one trending N. 35 o W . and dipping 75 o NE., the other trending N, 25 o E. and dipping 55 o NW. An extensive breccia zone about 10 feet wide is developed between the two bounding sheers. Exceptionally good quality turquoise forms veinlets up to three-quarters of an inch thick along the shears. Pyrite-bearing quartz veins are closely associated with the turquoise and while pyrite in Blue Gem is unusual to see, it is not unheard of.

Blue Gem turquoise remains some of the finest turquoise ever found, and unlike most turquoise mines, (in which the majority mined is chalky and only usable if stabilized) most of the turquoise found there is of a gem-quality grade. Today the Blue Gem mine is not viable because it sits in the middle of a huge mining operation. The emphasis at the surrounding mine is on precious metals and the extraction of turquoise is considered a hindrance in the mining process. The ever popular "Dump Diving" for turquoise through the overburden is not tolerated due to the very real danger of becoming buried in a slide. Insurance factors, equipment hazards, high explosives and safety issues along with a lack of interest from the mining company keep Blue Gem turquoise unavailable to the world, at least for now.

At Twin Rocks Trading Post, we possess a deep love for great American turquoise. Visit us under the red rock twins and we will teach you about the joys of collecting turquoise.